How Should Cambodia Respond to the Pressure from the West?

Written by: Vong Promnea, A Fresh Graduate with a Bachelor’s Degree in International Relations from the Royal University of Phnom Penh

Edited by: Dr. Heng Kimkong, Co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Cambodian Education Forum and Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Cambodia Development Center

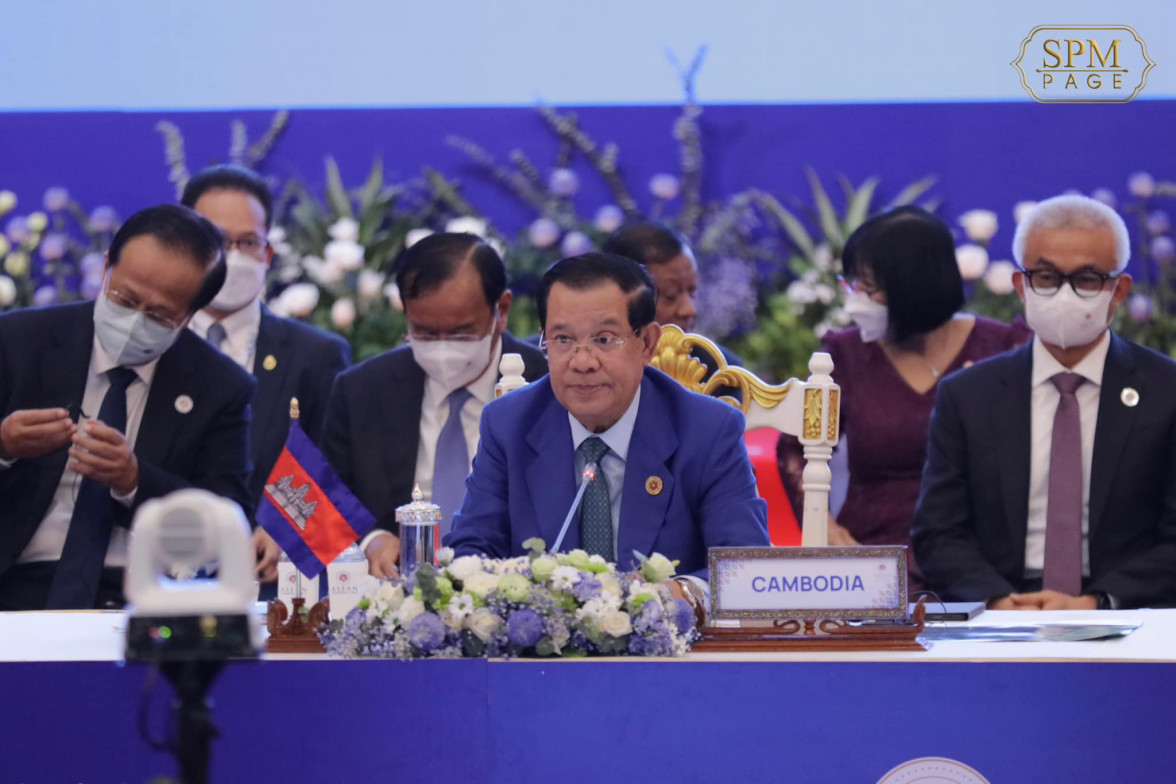

(Photo Credit: Facebook Page of Samdech Hun Sen, Cambodia Prime Minister)

Background

Until now, Cambodia has experienced pressure from Western countries for more than two years already regarding its latest development of human rights. Western countries have been using trade and economic sanctions as a means to require Cambodia to improve human rights. Two of the sanctions are the withdrawal of the Everything But Arms (EBA) of the European Union (EU) and the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) of the United States (US). Although they share similar aims to promote liberal democracy, these two tools are completely different in terms of their origins.

Since 2001, the EBA, one of the three branches of the Generalized System of Preference (GSP) of the EU, has been applied to the least developed countries (LDCs) to allow them access to the full duty-free and quota-free EU market for all products except weapons and armaments. Cambodia, as one of the LDCs, has gained substantial benefits from the EBA scheme for its economic development since 2003. Unfortunately, on 12 August 2020, the partial and temporary withdrawal of EBA from Cambodia became effective. This decision was triggered by “serious and systematic violations” of the core human rights in Cambodia including rights to political participation, freedom of expression, freedom of association and assembly, land rights, and labor rights.

The GSP of the US, on the other hand, expired on 31 December 2020. As of now, it has yet to be renewed by the US Congress and inevitably impacts Cambodia’s exports to the US as it is now subject to “most favored nation” status tariffs. In other words, Cambodia can no longer enjoy tariff reductions and exemptions on its exports to the US that it has received since 1997. The pending status of the renewal of GSP resulted from the call by two US lawmakers through their Cambodia Trade Act (CTA) in 2019 to review Cambodia’s eligibility. The renewal depends largely on the commitment of Cambodia to strengthen human rights and promote democracy.

EBA and GSP as human right conditions

This economic leverage has not only been utilized in Cambodia, but also applied to other developing countries across the world if the “serious and systematic violations” of human rights under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) are found. Basically, the “Enabling Clause” of the World Trade Organization (WTO) has allowed developed countries including the US and EU to grant GSP to LDCs or developing countries, and thus be eligible to put pressure on them. Research has shown that material capacity of great power, known as conventional approach, may facilitate the spread of new norms and promotion of international cooperation.

What makes the GSP of the US and the EBA of the EU different from others, noticeably that of China which is the major competitor of Western countries, is their connection with respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, sometimes known as “trade-human rights”. They allow the US and EU to link the GSP with human rights conditions and sometimes use restrictive conditions to link business objectives with political interests. Kimberly Ann Elliot, one of the economists interested in economic sanctions, pointed out that the motives behind the use of sanctions aligned with the three basic objectives of national criminal law: to punish, to deter, and to rehabilitate.

The inconsistency of the Cambodian government

The decision of the EU and US to impose trade and economic sanctions on Cambodia was inspired by their views that Phnom Penh would restore its current situation of human rights. However, the Cambodian government has not made a significant improvement to these issues, especially since the partial withdrawal of EBA on 12 August 2020. In terms of political discourse, Prime Minister Hun Sen has repeatedly claimed that the US and EU have used EBA and GSP to serve their political ambitions and use the human rights issue as a pretext for interfering in internal affairs and thus violating the sovereignty and independence of Cambodia that should be respected under the UN Charter.

In addition, rather than finding solutions, Cambodia continues its actions that are considered as attributions to the recent development of human rights. For instance, in the latest report of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR), the space to exercise fundamental freedoms in 2021 was still limited. CCHR used freedom of expression, freedom of association, and freedom of assembly as indicators to measure the progress, which are almost consistent with the core human rights needed to be restored in Cambodia. In this regard, the report demonstrates the unwillingness of the government to reconsider that pressure and especially the action plans that were proposed by the EU and the US.

The consequences of the sanctions

The reluctance of the Cambodian government to lessen human rights problems has not only worsened the consequences of EBA withdrawal and the pending status of GSP, but also impacted diplomatic relations with the West. Most people believe that Cambodia would experience a serious economic crisis in many industries and thus could directly affect its average growth rate. For instance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected in late 2019 that the withdrawal of EBA would lead to a 3 percentage point decline in the growth of Cambodia’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product). This does not account for indirect effects, which may be substantial. These preferences are crucial to Cambodia because they have enabled the country to benefit from competitive advantage, promote economic development, and create employment opportunities.

The projection has been correctly proven as the GDP growth of Cambodia has declined from 7.1% in 2019 to 3% in 2021, although it has been coupled with the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the report of the World Bank in 2022, it is found that the export of Cambodia to the EU market declined from 28.1% in 2019 to 19.2% in 2022, partly due to the partial withdrawal of EBA. Furthermore, at the same period when the GSP of the US for Cambodia also expired, Cambodia’s exports to the US have increased from 27.6% to 44.7%. However, it has not come without costs. Cambodia has faced the tariffs imposed by both the EU and US that could impact the revenue, in addition to its consequences for the employment sector.

The alternatives that have been defended by the Cambodian government, for example, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Cambodia-China Free Trade Agreement (CCFTA), would not substitute the benefits that Cambodia has enjoyed under the EBA and GSP preferences especially in the short run. Moreover, Cambodia is losing its international legitimacy as a result of this serious and systematic violation of human rights. Nonetheless, these are not including the uncertainty of the future and the closer monitoring of the EU that can lead to the full withdrawal of the EBA.

What should be done?

In light of these consequences, it is necessary for Cambodia to address issues of core human rights that are crucial not only for realizing human rights – one of the core missions of the Cambodian government, but also for restoring the GSP schemes of the EU and US.

- Firstly, the Cambodian government as the duty-bearer should firmly tackle unresolved and ongoing disputes caused by the ineffective implementation of human rights. An integrative approach should be an option so that all parties can mutually benefit from the settlement.

- Secondly, laws or regulations that restrict exercises of fundamental freedoms should be reversed and refrained from enacting. Otherwise, Cambodia would lose the dynamics of such exercises essentially from Cambodian youth.

- Lastly, politicians of Cambodia should not perceive the motives of trade and economic sanctions as a Western way of modern imperialism, yet as a loophole of democratization that needed to be closed by collaborating constructively with relevant stakeholders.

* This blog is produced with the financial support from the European Union and The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency through Transparency International Cambodia and ActionAid Cambodia. Its contents do not reflect the views of any donors.